Published on September 9 2025 In Scientific news

Where does Arctic char live in winter?

An article by Valérie Levée, science journalist.

When the Inuit go fishing for Arctic char on the frozen lake, they know when and where to cast their lines to get a bite, because for centuries, they have passed down fishing sites from generation to generation. But climate change could throw a wrench in their plans by altering the physical environment of the lakes and, therefore, the char's habitat. While a doctoral student in Professor André St-Hilaire's laboratory at INRS, Véronique Dubos studied the conditions under the ice that are conducive to Arctic char life in winter and published her research in Arctic Science.

This is an important issue because this fish, rich in fatty acids, is an essential part of the Inuit diet. In fact, Isabelle Laurion, also a professor at INRS who collaborated on Véronique Dubos' project, is continuing this research as part of the FROST project funded by NordForsk and ArcticNet. "We are studying the effect of shorter winters on habitat quality and char health in a dozen circumpolar lakes in six northern countries. Using lake morphology, temperature, oxygen concentration, and light, we aim to characterize and model fish habitat and then make projections for the future," explains Isabelle Laurion, co-researcher on the FROST project.

Véronique Dubos focused on lakes in Nunavik near Kangiqsualujjuaq, and she is particularly interested in the winter habitat of Arctic char because this fish is anadromous, meaning it spends the summer in saltwater at sea and winters in freshwater lakes. It does not have the antifreeze protein needed to withstand saltwater temperatures that can drop to -1°C, so it must swim upriver to find freshwater above freezing. The fry are born in freshwater spawning grounds and remain there for their first three years, feeding and gaining weight before heading out to sea. Adults do not eat during the winter because their digestive system is atrophied. For Véronique Dubos, the question was not “what does a char eat in winter,” but rather “where does a char live in winter” in terms of depth, temperature, and oxygen concentration.

Relying on Inuit knowledge

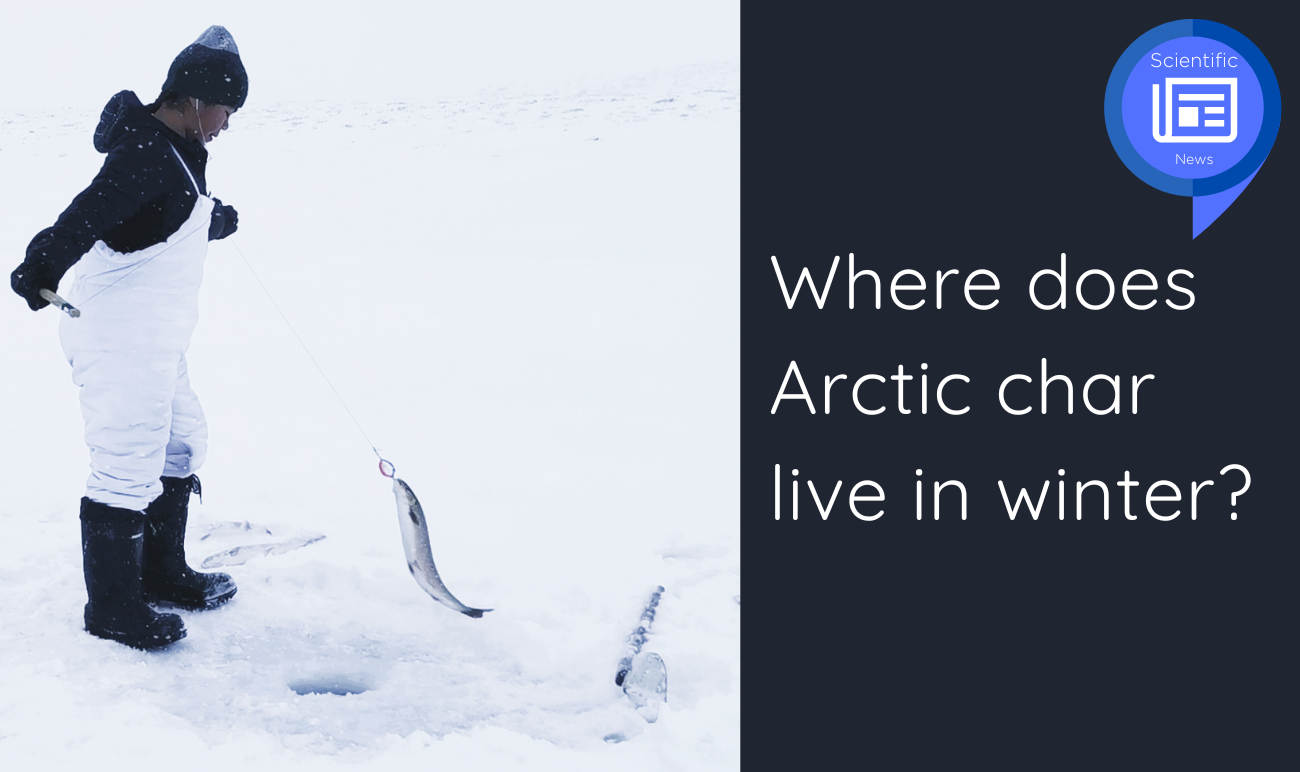

A conventional methodology would have been to systematically survey the lakes, quantify the presence of char, measure the temperature and oxygen concentration, and look for possible associations between the physical characteristics of the water and the presence or absence of fish. This was not the methodology followed by Véronique Dubos, who chose to rely on Inuit knowledge to identify fishing sites as locations where char are present and therefore their habitat. Conversely, areas where the Inuit do not fish are considered to be sites where char are absent.

“The premise is that fishermen know where the fishing grounds are, and there are places they don't go because there are no fish there. They're not going to waste their time fishing where there are no fish. The idea was to rely on that information. It's reliable knowledge,” says Véronique Dubos.

In addition to fishing sites, spawning grounds were also identified, which are also known to the Inuit of Nunavik, as they also consume char eggs.

Véronique Dubos therefore compared the characteristics of spawning grounds, fishing sites, sites with no fish, and sites with fresh water. “It's interesting to characterize the current habitat and quantify future changes to see if these habitats are sustainable in terms of providing abundant, high-quality fish,” adds Isabelle Laurion.

Integrate the measurement protocol into fishing activities

Véronique Dubos developed her measurement protocol with fishermen she knew from previous work and who volunteered to participate in the research. Based on the principle that the protocol should not disrupt fishing operations or daily activities, she designed a measurement system that was compatible with fishing equipment. “I watched how they fish so that my instruments could be adapted to their nets,” says Véronique Dubos. “When scientists want a lot of detail, it can quickly become laborious. It had to remain simple for it to work,” confirms Isabelle Laurion. Similarly, the fishermen did not have a schedule or timetable to follow when taking measurements. They went fishing as needed and, incidentally, took measurements in the water column beneath their feet. However, for the purposes of the study, the fishermen also agreed to dip their lines and measuring instruments into the absence sites. But knowing that the fish would not bite, the fishing effort was less, which is an issue for comparing sites, acknowledges Véronique Dubos. However, she supplemented the measurements with visual observations using an underwater camera.

A fraction of a degree that makes all the difference

The measurements reveal no significant difference in temperature and oxygen concentration between sites where the fish is present and those where it is absent. Char are content with a temperature of around 0.2°C and dissolved oxygen saturation of 91%. However, this fish tends to settle in coastal areas, on gently sloping bottoms, at an average depth of 4.1 m and under a thin layer of snow.

The surprise came from the spawning grounds, located at an average depth of 3 m with a bottom temperature of 0.6°C, while sites without spawning grounds have an average depth of 6 m and a bottom temperature of 0.3°C. This is surprising because under the ice of lakes, between 0 and 4°C, there is a thermal inversion of the water, which should therefore be warmer at 6 m than at 3 m. The researchers hypothesize that slightly warmer water arrives in the spawning grounds, which the char are able to sense in order to spawn. This tiny difference in temperature could prevent the eggs from freezing. The thinner snow cover at these sites could also promote photosynthetic activity and the presence of food for the fry.

It is only a fraction of a degree, but it is relevant information for the Inuit, who are considering seeding lakes with eggs rather than fry. It makes sense to deposit the eggs in conditions favorable to their development.

Recommendations from researchers

- Inuit fishers and hunters have a better understanding of the territory than any scientist. We need to work with them and their knowledge.

- We need to be patient, which is not in the nature of scientists who want things to happen quickly. We need to counteract this tendency and take the time to listen in order to collaborate more effectively.

For more information

Publications by Véronique Dubos

On the habitat of Arctic char in winter

- Dubos, V.,André St-Hilaire, A., Isabelle Laurion, I., et Normand E. Bergeron, N. E. (2023). Characterization of anadromous Arctic char winter habitat and egg incubation areas in collaboration with Inuit fishers. Arctic Science, 10 : 215-224 https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2023-0008

On the apparent winter disappearance of char. Their near immobility makes them difficult to catch.

- Dubos, V., Gillis, C.-A., Nassak, J., Eetook, N., et Moore, J.-S. (2024). Winter and spring movements of anadromous Arctic char : Linking behavior to environmental conditions through an Inui-led telemetry study. Environmental Biology of Fishes, Juillet 2024https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-024-01572-9

Videos by Véronique Dubos

- Arctic charr that have just arrived at their winter lake, a few weeks before the breeding season : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Hi5hf104mA

- Arctic char filmed at a site where they are present under the ice in winter during surveys : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0bnawtOkTV4

Arctic char filmed at a site where they are present under the ice in winter during surveys

A study of coastal areas when the ice begins to melt, providing potential explanations for how char use the coastline.

Bégin, P.N., Rautio, M., Tanabe, Y., Uchida, M., Culley, A.I., et Vincent, W.F. (2020). The littoral zone of polar lakes: inshore–offshore contrasts in an ice-covered High Arctic lake. Arctic Science , 7(1): 158–181. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2020-0026

A study showing the advantage of having slightly higher temperatures for egg incubation.

Jeuthe, H., Brännäs, E., et Nilsson, J., (2016). Effects of variable egg incubation temperatures on the embryonic development in Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus. Aquaculture Research 47, 3753–3764. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.12825

Photos: Véronique Dubos

Back to news